“Less than 100m back! Brown bear! You need to move, don’t stay here!”

Less than a minute after surviving the descent, I been standing, marvelling at the beautiful green pine forest which I had came to a halt in. It was a vivid contrast from the depressed, gnarled birch trees I’d been seeing for weeks. Then, the roar of a snowmobile, getting louder as it stalked up to me from behind. The rider stopped, and started to shout at me. And for good reason.

I had actually seen bear prints, albeit distorted from the rain. I had decided I was being paranoid to think they were anything more sinister than human footprints. Bears in this region normally hibernate until late May, and this was only March. But the heat meant this bear had woken up early. A worrying reminder of climate change: the weather had peaked around 30°C above where it usually was at this time of year.

But I had bigger concerns than climate change at that moment. I had planned to to camp almost at the exact place where I was stood. While I was now eager to keep moving, I was a bit stirred by this episode. I normally cooked and kept a lot of food in tent with me: the exact opposite of what you should do in bear territory.

And with the bear having fasted for over five months, and my dinner involving chicken gravy, it felt like I was one passer-by away from a living nightmare. I decided I’d be much more careful with how I stored food in future to reduce the risk, but it left me slightly on edge.

Skiing on, I passed another Sámi snowmobile rider, and warned him of the bear further up the trail. He grinned as he reassured me I should keep well away from the area: “yes, the bear will be very, very hungry!” I decided to camp as close to town as possible.

Karasjok was a shorter stopover than Kautokeino, in the end no rest day, but a few hours in town. Wandering around, it was interesting to see the sights of the Sámi capital: this included the local Sámi parliament. Unfortunately most things were closed on weekends, so after a look around, and grabbing some supplies for pulk repairs, I left.

I had figured that I could easily average about 20km per day at this point, so opted to book my flight back from Kirkenes based on that assumption. The problem with fjellski though, is that the slightest change in conditions can change your progress from an easy 20km per day, to fighting tooth and nail to get even half of that.

And the weather definitely had other ideas. It turned nasty, straight after I left town.

Leg 3 Karasjok to Tana

Days of headwinds, blizzards and white-outs. Pushing through deep powder, off-trail, the pulk acting like an anchor as it sunk deep into the loose snow. Exhausted at the end of each day, progress slowing further. Legs getting more and more fatigued. Zero-visibility, navigation becoming harder, and the pace dropping even more. But I knew I just had to keep moving, and hope that conditions improved: get my head down and get on with it. Every step I did, was one closer to finishing.

And eventually, a few days later, the weather did ease and the snow underfoot became more solid, more wind-blown, as I climbed above the treeline into the mountains. It became easier to move, visibility started to improve, and eventually the wind eased too.

After the difficult start, this became my favourite section of the trip, the most remote feeling of them all. Skirting around the base of the mountains, as they started to poke through the clouds, one by one. The sun also returned, and I started to make up for the lost time. Some new ravine crossings, but I found safe routes through, and managed to avoid any other calamaties.

Mind Games

Although the peace was nice, in hindsight, I’d say isolation was starting to have an effect on me at this point.

On one hand, I had seen more people than I’d expected during the trip, the prospect of a month alone in the Arctic wilderness hadn’t totally materialised. At times I started to feel annoyed at how difficult it is to feel truly remote in this day and age: I had rarely been more than a few days away from hearing the whine of a snowscooter.

But from the point of isolation, the odd bit of small-talk isn’t a long-term substitute for companionship. The length of time alone definitely made me re-evaluate how important friendships, family and relationships are. I was starting to think of small interactions with friends back in civilisation: similar to fasting, and dreaming of food.

Imagining going to a pub, drinking even one pint with a friend, being around people, having a conversation. Luxury!

This thought went round in my head for hours, imagining how nice it would be, thinking of all the little details: the specifics of the pub’s interior, the woodwork, the ceiling lights; which beer I was drinking, its taste. It felt a little like a mirage.

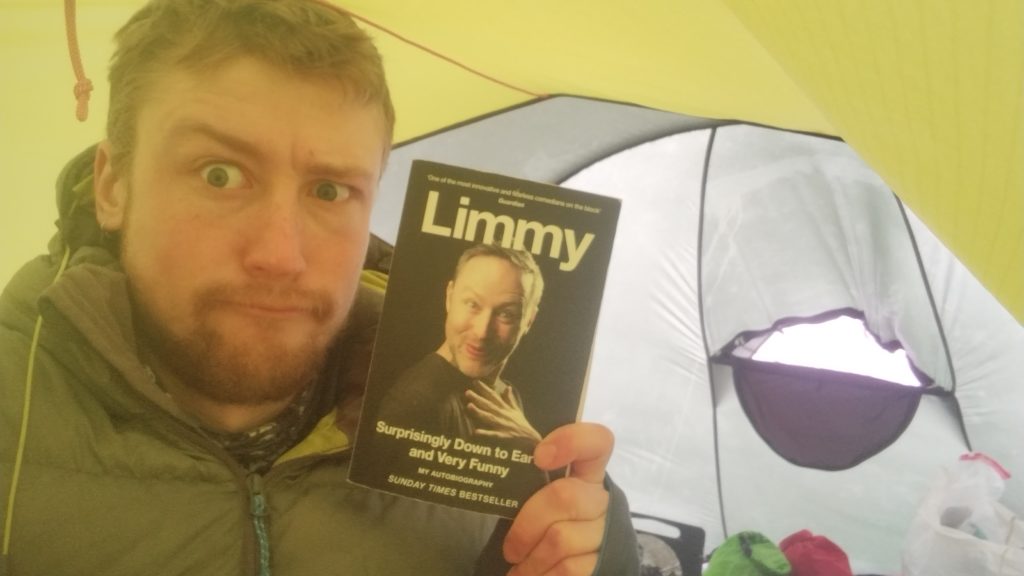

There were things I’d preemptively done to stave off potential feelings of isolation. Podcasts were a big one, having downloaded hundreds of episodes to an MP3 player. Just hearing a human’s voice for an hour can make a big difference, and it definitely helped.

But the longing was still there, to be with people. Humans are, after all, a social species.

Reflecting on this aspect of the trip, I’d say the isolation wasn’t necessarily a problem, but it did affect me more than I realised or expected, creeping in stealthily at times.

And the million dollar question, would I do a solo trip of this timeframe again? It certainly would have been a lot more fun with others: it’s nice to have shared experiences. But, as I sit here writing, something about the peace of being alone, the vast emptiness of the Arctic, and the challenge of being alone for so long, seems to be drawing me back.

As I descended from the Tana mountains, reaching the end of this stage, more bad weather was forecast. The previous storm had meant the food situation was looking pretty tight if I got caught in another storm. So I briefly skirted into Finland, a case of casually walking across a frozen river to Lapland, for a few extra supplies in case I ended up tent-bound for a day or two.

With the supply situation sorted, I just had to get my brain in gear, and get ready for the last push. I was ready to start the final section, the end was in sight.

Continue Reading: The Long Haul – The End, At Last

[…] Continue Reading: The Long Haul – Finalé […]

[…] Continue Reading: The Long Haul […]