Land

We were flying through a thick blanket of cloud. We dropped in altitude, some black crags briefly appeared before being swallowed up again. My first sighting of this alien land. I could barely hold in the excitement that that fleeting glimpse had whipped up inside me. This place had been in my mind for years. A place of almost mythical status.

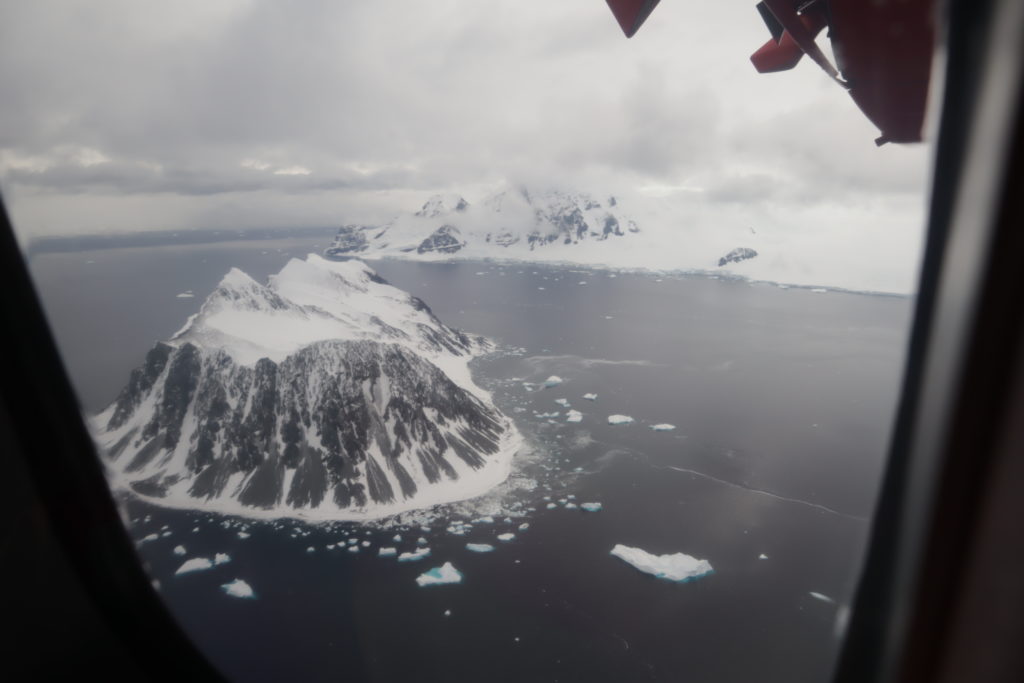

The plane slowly spiraled down, letting me absorb more of the surroundings. Crags, cliffs, barren islands, snow fields, glaciers. Everything shades of white, blacks and greys; all of it unbelievably wild. I didn’t know where to look.

We circled another few times, slowly coming in towards our final approach. A crunch as the wheels hit the dirt runway, before coming to an abrubt halt – the immersion suits thankfully being an unnecessary precaution.

The pilot hopped out of his seat and turned to face us. “Welcome, to Antarctica.”

Antarctica, it probably goes without saying, is not an easy place to get to. I had tried years ago to get funding for an expedition of my own to Antarctica. An incredible amount of planning and preparations, endless emails and phonecalls. But the sort of money involved is eyewatering, and sponsors were far from queueing up. I eventually resigned myself to the fact I’d tried hard, but it wasn’t to be. Expedition planning became nothing more than an untouched folder on my hard drive.

But sometimes in life, things take a lucky turn. A lot of stars aligned all at once. A job advert and a round of interviews, leading to a new employer and a new city. Months passed. Then a passing conversation at work: how would I feel about leaving for a field project, deep in Antarctica, in three weeks’ time?

I didn’t need to be asked twice. Dropping everything, packing, and getting myself ready. A series of flights down to southern Chilé, then waiting for an aging aircraft to take us across to the icy continent.

And here I was. It was real. Despite the exhaustion of all the travels, I was running on pure excitement. A first walk around the station: giant icebergs, seals lazing out on ice floes. There were Adélie penguins all around the rocky peninsula: an inquisitive little group of them running right up to us to get a look at the new faces in town. It all seemed like a fever dream.

The next few days passed in a blur. A huge mix of different training sessions: glacier travel, crevasse rescue, co-piloting an aircraft, snowmobile riding, Antarctic tent craft, meteorological observing. And that was all on top of trying to get to grips with the concept of ice drilling – the job I’d been asked last minute to fill in for.

But it wasn’t all work and no play. I took every chance to go for a ski, or a walk around the peninsula to watch the incredible wildlife and scenery; nights in the bar, hearing crazy tales from years gone by. Just immersing myself in the surroundings, in the history of this place. Old black and white photos dotted around, the frames made from old sledges with incredible stories of their own.

The sad thing was knowing that this phase wasn’t to last for long: if I’d had it my way I’d have been happy to have spent weeks there, and it still wouldn’t have lost that magical feeling. But we were on a schedule, this was merely a stop off en route to a desolate glacier which would become home for the next six weeks.

I was apprehensive about what was to come next: how would I cope with the Antarctic conditions , the people, the isolation; how would I manage trying to operate machinery I’d never even laid eyes on before. But this was an adventure, there was no backing out now, and nothing great ever happened by just sitting around.

As the days went by, apprehension built as we waited to hear when we’d be flying. We were just one project in a much wider web of science projects: ice drilling, geological sampling, logistical efforts, remote instrument servicing. Planes, ships, tracked vehicles – we were a small cog in a much larger operation. We would just have to wait until our time came.

The call came suddenly: there would be an attempt the next day to get two of us out. I’d been chosen to accompany our field guide to set up an advanced camp in preparation for the other four. A storm was forecast shortly after, so we’d likely be waiting for several days before it’d be safe again to fly the others in to join us.

I went to bed, but didn’t sleep much. Excitement, and a head full of what-ifs. The morning came round, a big part of me hoping for another few days of respite and relaxation, proper food, showers and laundry, before potentially six weeks of deprivation. But a grin and a final thumbs-up from the weather forecaster. It was on.

Three of us and the pilot traipsed over to the hangar to join the packing effort. I couldn’t believe the amount of stuff we were ramming into the back of the plane. It just didn’t end. Sleds, tents, food boxes, jerry cans, radio boxes, satellite phones, more food, fuel. It reminded me of weekends cramming too much caving equipment, and cavers, into the back of someone’s car before a long journey. I didn’t expect to experience the same thing flying in Antarctica.

I clambered into the co-pilot seat, sitting well clear of all the instruments. Some pre-flight checks, and we taxied onto the runway. This was it. Final checks. Permission to take off?

Permission granted. Engines thrust into full bore, and off we went, the water like glass, the sun beaming down. Into the unknown.